It’s a perilous combination for 165 million people with employer-sponsored health insurance. Premiums are rising, while yearly pay raises shrink.

Rising Obamacare premiums are a political problem for Republicans. Rising premiums for workers who get health insurance from their employers could be an even bigger one.

Republicans in Congress are focused on finding a way to counteract an expected 26 percent rise in premiums for people who buy insurance through the Affordable Care Act, without extending government subsidies that make insurance more affordable.

What the GOP isn’t talking about: Nearly seven times as many Americans get health insurance through an employer as those who buy it individually. Those 165 million people are expected to see their premiums spike by up to 7 percent.

“That’s going to absolutely put pressure on whoever’s [in power],” said Katherine Hempstead, senior policy adviser at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, a health care-focused philanthropy.

Voters have started making it clear that affordability of basic necessities — including health care — will be a defining issue in determining who holds the balance of power in Congress after next year’s midterm elections. That means the GOP may need to look beyond fixing Affordable Care Act subsidies to maintain control of the House and Senate.

Meanwhile, Democratic lawmakers and candidates say they plan to make affordability their top issue in next year’s midterm elections, but it remains to be seen whether they’ll include the plight of workers with employer-provided insurance in their push.

Passing rising medical costs on to patients

People with group coverage are expected to see an average 6 to 7 percent premium increase this month as they re-enroll in coverage that will start in January.

That comes as their employers are expecting the largest jump in health costs in 15 years in 2026, at 6.7 percent, more than double the rate of inflation and the typical pay raise workers are getting.

Employer-provided insurance rates are rising as medical costs shoot up — especially hospital and prescription drug costs, partially driven by the GLP-1 drug boom. In 2025, prescription drug spending rose 9.4 percent on average among large employers as more companies began covering the costly weight-loss treatments, according to Mercer.

Consolidation among health care providers, which limits competition and gives health systems more power to demand higher prices for care, also plays a role, policy experts said.

Plans may be more expensive next year to account for uncertainty over rising costs as the Trump administration implements tariffs on some drugs and medical devices, the experts said. That could drive up costs for providers at the same time that fewer Americans are projected to be insured, which puts pressure on health systems to shift costs to commercial plans.

“We all use the same delivery system, and if a hospital loses Medicaid coverage or other public coverage, they always seek to recoup those costs by passing them on to private coverage,” said Elizabeth Mitchell, president and CEO of Purchaser Business Group on Health, a nonprofit coalition of employers.

Congress is ‘missing the broader point’

The 24 million people enrolled in Obamacare and 69 million seniors enrolled in Medicare are also seeing higher premiums during open enrollment. While there are similar catalysts behind the price hikes, Obamacare premiums are under extra pressure due to expiring subsidies Democrats supersized in 2021.

The news gets worse for those on employer plans.

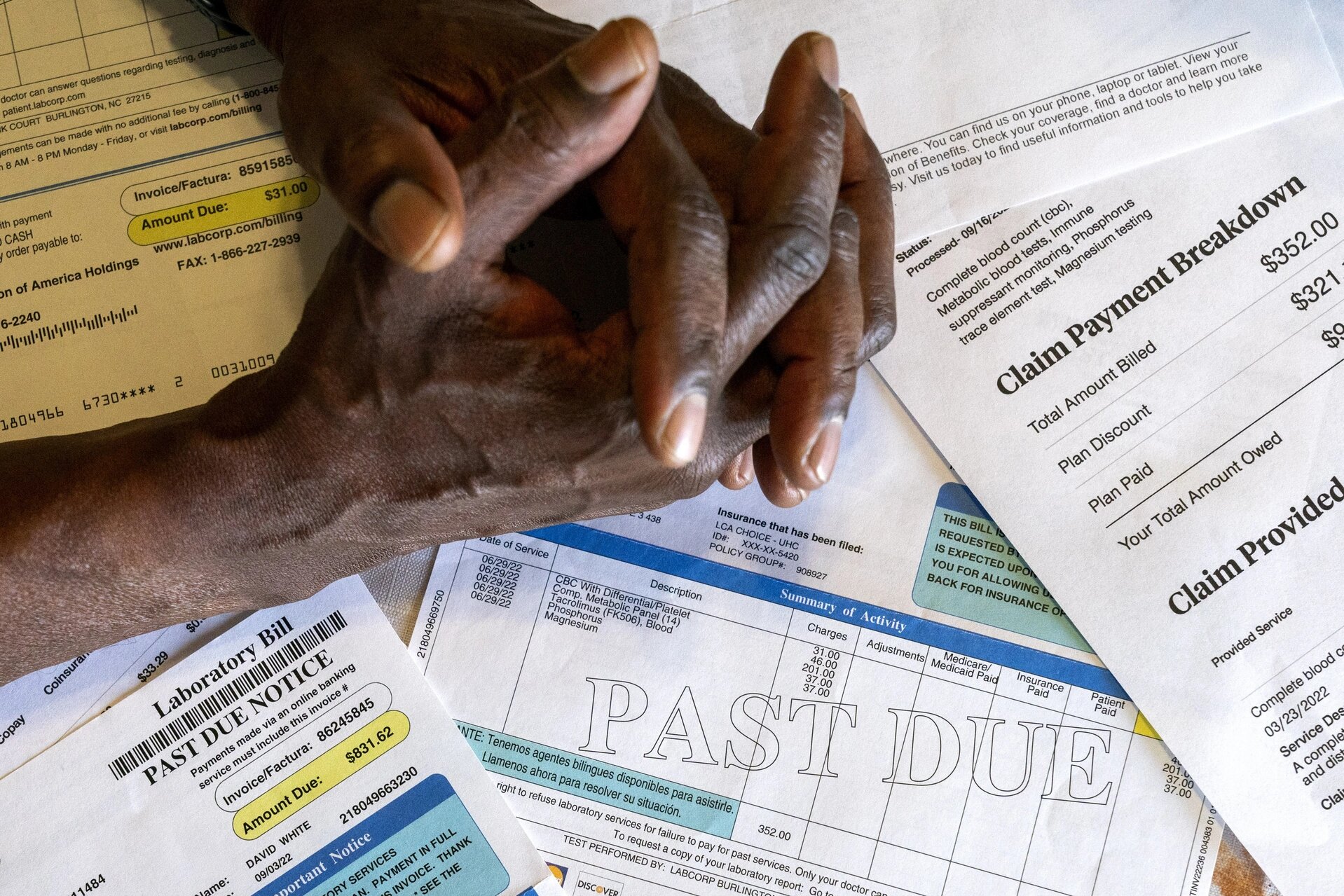

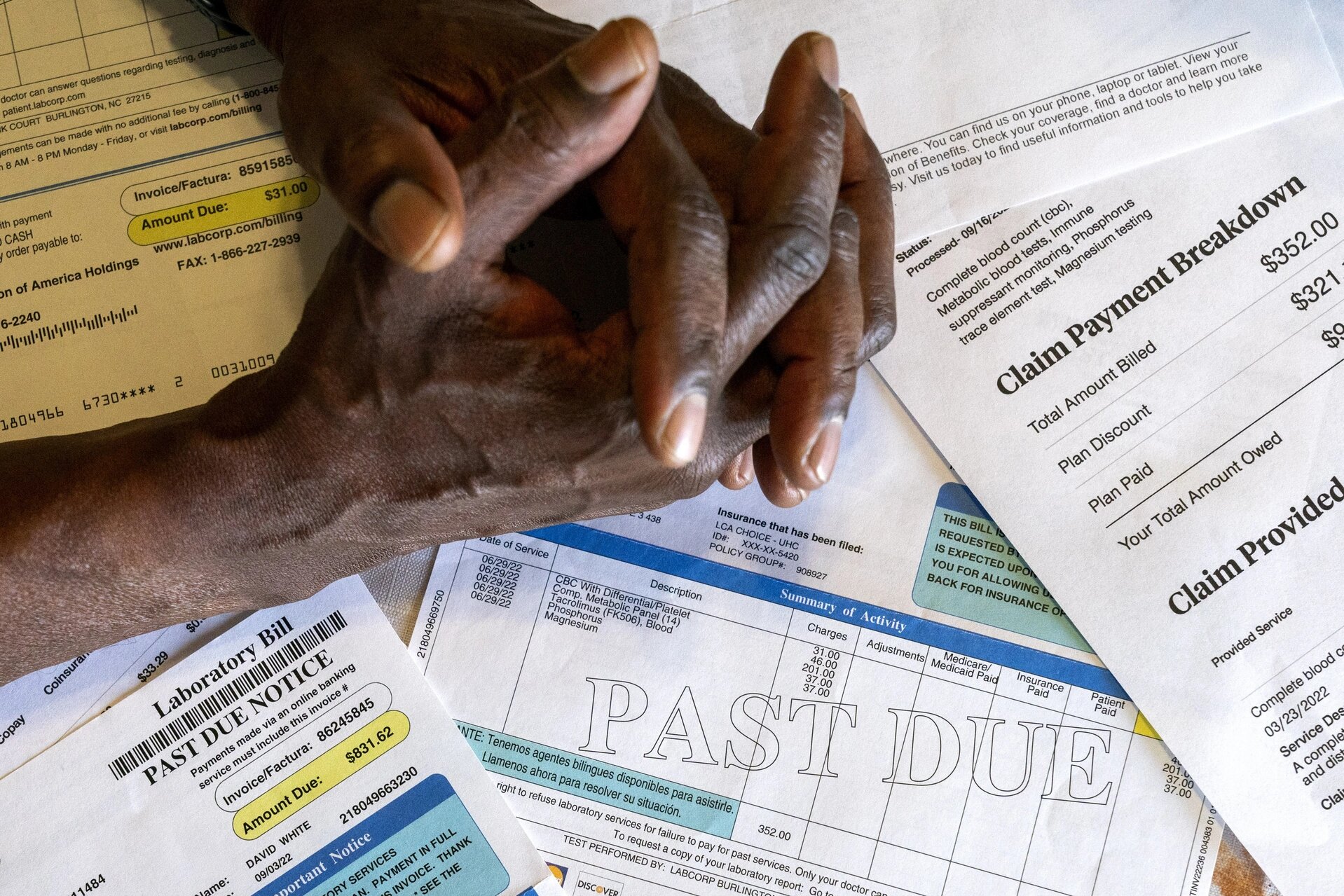

In addition to rising premiums, workers are expected to see higher deductibles, co-pays and out-of-pocket maximums next year, which could lead to larger out-of-pocket costs, according to consulting firm Mercer’s 2025 National Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Plans.

The projected premium increases for next year in the employer market follow a 6 percent increase this year, when premiums for employer-sponsored family coverage reached nearly $27,000. Workers contribute an average $6,850 toward the cost of family coverage, according to nonpartisan research group KFF, with their employers picking up the rest.

Employers plan to raise wages 3.1 percent on average in 2026, according to Mercer. That means a sizable portion of many employees’ pay increase will go toward covering rising insurance premiums, leaving little left over to pay for increased costs elsewhere in their budgets.

“Our wages aren’t going up fast enough to keep up with inflation. A huge part of that is because [employers] are spending so much more on health care,” said Shawn Gremminger, president and CEO of the National Alliance of Healthcare Purchaser Coalitions, a coalition of mid- and large-sized employers.

Concern from employer groups like the National Alliance and PBGH comes as bipartisan lawmakers in Congress are searching for a path forward to make health care more affordable for millions of Americans — but the focus is on the Obamacare marketplace.

Lawmakers are “missing the broader point,” Gremminger said.

Average Americans aren’t going to understand the nuances of health care markets and subsidies, he said, adding, “But I think they will notice when their health care costs go up next year, and they will wonder why Congress is congratulating itself on solving the problem that they haven’t solved.”

Employer groups are urging Congress to consider cost-cutting reforms, including bolstering provider and insurer price transparency requirements and cracking down on health care consolidation. But so far, there’s been little indication that either party is focused on employer health costs as Obamacare subsidies take center stage of lawmakers’ end-of-year discussions.

Republicans recently proposed allowing people enrolled in the ACA to access funds through health savings accounts, as opposed to receiving a federal subsidy to offset premium costs. Democrats continue to push for an ACA subsidy extension.

Earlier this year, the Senate stripped provisions from the House-passed GOP domestic policy megabill that would have strengthened HSAs for people on employer health plans, including one that would have doubled the amount individuals and families could contribute to the pre-tax accounts for medical expenses that some companies offer with high-deductible health plans. Another stripped provision would’ve broadened services enrollees can use HSA funds for to include fitness and sports expenses.

The Senate-passed version of the bill included less expansive HSA provisions, including one allowing high-deductible plans to pay for telehealth visits without jeopardizing clients’ ability to qualify for HSAs. Another allows people to use HSAs for direct primary care, or when patients pay primary care doctors a monthly or yearly fee rather than reimbursing them through insurance.

House Ways and Means Chair Jason Smith (R-Mo.) signaled Monday that he wants to revisit the House’s HSA proposals and address rising employer health plan costs, but it’s not clear whether he plans to offer a specific plan and when he’ll pursue it.

Smith’s office didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Meanwhile, Republicans are looking ahead to the midterms. If they want to hang onto their majorities in the House and Senate, GOP lawmakers could stand to gain from addressing rising costs of employer insurance.

It’s among the priorities Americans say they care about, with polling showing that health care affordability is among the top issues voters hope Congress will address. The polling, from Reuters/Ipsos, also showed that voters see cost of living as a top concern going into the midterms.

Faced with rising costs from all angles, employees may opt to enroll in cheaper, lower-quality health plans with higher deductibles or forgo coverage altogether, a trend policy experts think will be mirrored in the ACA market if enhanced subsidies expire.

Consumers are already struggling to pay for basic expenses like food and gas, Hempstead pointed out. If they’re hit with a big increase in premiums, she added, they may say: ‘I’m just not going to pay for it.”

The result could be a lose-lose situation: Fewer people insured and more uncompensated costs for providers.