The president’s one-man-show approach to policy has sidelined Congress, agencies — and a whole K Street culture.

Intel Corp. looked like a winner in the Washington lobbying game at the start of 2025.

The federal government was set to funnel more than $10 billion to the American microchip giant, thanks to a long influence campaign by the company’s executives and hired Washington hands, who spent three painstaking years lobbying Congress, federal agencies and White House advisers.

Just a few months later, when a political controversy over the CEO’s links to Chinese companies put Intel’s deal with Washington in jeopardy, the whole drama was resolved in two weeks. And this time, the company’s path ran through just one person: President Donald Trump.

The sharp change in how Intel navigated Washington is being replicated across industries in Trump’s second term — by pharmaceutical companies cutting drug pricing deals with the White House, tech giants hoping to sell regulated equipment to China and energy firms that want looser environmental and permitting restrictions.

After decades of revolving-door culture, Washington is grappling with a new normal for how influence works in the capital. POLITICO spoke with several dozen lobbyists, industry officials and public relations professionals who revealed a transformation far more disruptive than the typical churn that comes with a new administration.

In Trump 2.0, American policy influence has shifted from its previous channels — agency officials, top lawmakers and staffers on key congressional committees — to a new reality where change comes suddenly from the top.

The president and a handful of lieutenants have seized full control over policies once considered the remit of Congress and experts at agencies, including hyperspecific issues like tariff rates, high-skilled visa fees and funding freezes. Trump’s gravitational pull has forced CEOs to act as their companies’ top lobbyists, plying the president with gifts and concessions to secure their policy priorities.

“The C-suites of America are now getting a first-hand opportunity to bang their heads against the wall,” said Niki Christoff, a tech consultant with stints at Salesforce and Google.

The new dynamic has transformed the business of Washington influence, shutting out many veteran lobbyists and excluding even longtime experts from the most important policy fights in Washington. With Congress and the agencies often sidelined, outside lobbying firms and in-house specialists — many with decades of policy experience and cross-party relationships — are declining in importance.

The example of Intel shows that direct personal lobbying can be strikingly effective — but also come at an enormous, and often unexpected, cost. After CEO Lip-Bu Tan was directly threatened by Trump in a social media post over his investments in Chinese companies, he flew to Washington, met personally with the president and agreed to hand the government nearly $10 billion in Intel stock to keep the company’s government subsidies alive — a measure not required by any law.

Similarly, the CEO of chipmaker Nvidia, Jensen Huang, built a personal relationship with Trump and ultimately won the right to sell chips to China — but only by giving the government 15 percent of its sales.

Their unusual concessions suggest that even CEOs with White House connections are struggling to adapt to a Trump-centric policy paradigm.

“In this administration, showing up is necessary but not always sufficient,” Christoff said.

‘A D.C. that doesn’t exist anymore’

Most lobbyists who spoke to POLITICO described the old levers of Washington influence and intelligence as increasingly broken, starting with Congress. The legislative branch is losing importance as Republicans — in charge of both chambers — take their cues from the White House to a degree that’s unprecedented in modern politics.

“Congress has basically taken itself out of the equation,” said Rich Gold, a Democrat who heads lobbying and law firm Holland & Knight’s public policy and regulation group. “There is a perception that Democrats have not fought back, and Republicans have basically ceded all their authority to the president.”

The same is true at federal agencies, which once operated more independently but are now closely responsive to the president himself.

From K Street’s point of view, there’s only one lever consistently worth pulling — and it sits in the Oval Office.

Lobbyists who can’t get clients in front of the president are struggling to adapt. Longtime lobbying heavyweights with extensive policy chops and Hill acumen — firms like Akin Gump and Holland & Knight — are facing greater competition from newer firms, like Ballard Partners, with direct lines to Trump and his aides.

And industry trade associations, once the crucial eyes and ears of member companies, are largely flying blind.

“The old school, establishment firms in D.C. don’t understand the new Washington,” said one lobbyist close to the administration, granted anonymity to candidly discuss the business landscape. “They are used to a D.C. that doesn’t exist anymore. It’s a different ball game from 10 years, or even five years ago.”

“After [Trump’s] first administration, they thought that the Trump movement would never come back,” said Carlos Trujillo, a former Trump administration official and president of lobbying firm Continental Strategy. “Now a lot of clients whom they’ve advised for years on their opinion of what’s happening … have lost faith and confidence in their understanding of government, and particularly Republican politics.”

The White House is aware that lobbyists are frustrated at being shut out of policy decisions — and one administration official called it a feature, not a bug, of Trump 2.0.

The official, granted anonymity to discuss sensitive relationships, said that if lobbyists or their clients are upset about a presidential proclamation, they can always work out details after the fact — though corporate leaders should be prepared to give Trump something in return.

Companies that can’t get their CEO into the Oval Office are searching frantically for new ways to capture White House attention. They’re increasingly turning to PR and advertising firms that can spread their message across television channels, social media accounts and podcasts popular with Trump and his lieutenants. Washington lobbying shops are consequently beefing up their PR and ad wings.

“Having a podcast ad on the Lex Fridman show, having a full-page ad in the New York Post, having a digital ad campaign on Facebook surrounding people close to the president who aren’t in the administration — that is more like inception than direct advocacy,” said Christoff. “And it’s a new paradigm for Washington influence.”

A president who intervenes

The opinions of presidents and White House advisers have always been important to federal policymaking, and to anyone trying to influence it. But presidential power was historically felt at 30,000 feet, leaving experts in government and industry to hash out thorny details.

Toggle menu

‘He’s micro-managing phenomenally’: How Trump grabbed all the levers in Washington

The president’s one-man-show approach to policy has sidelined Congress, agencies — and a whole K Street culture.

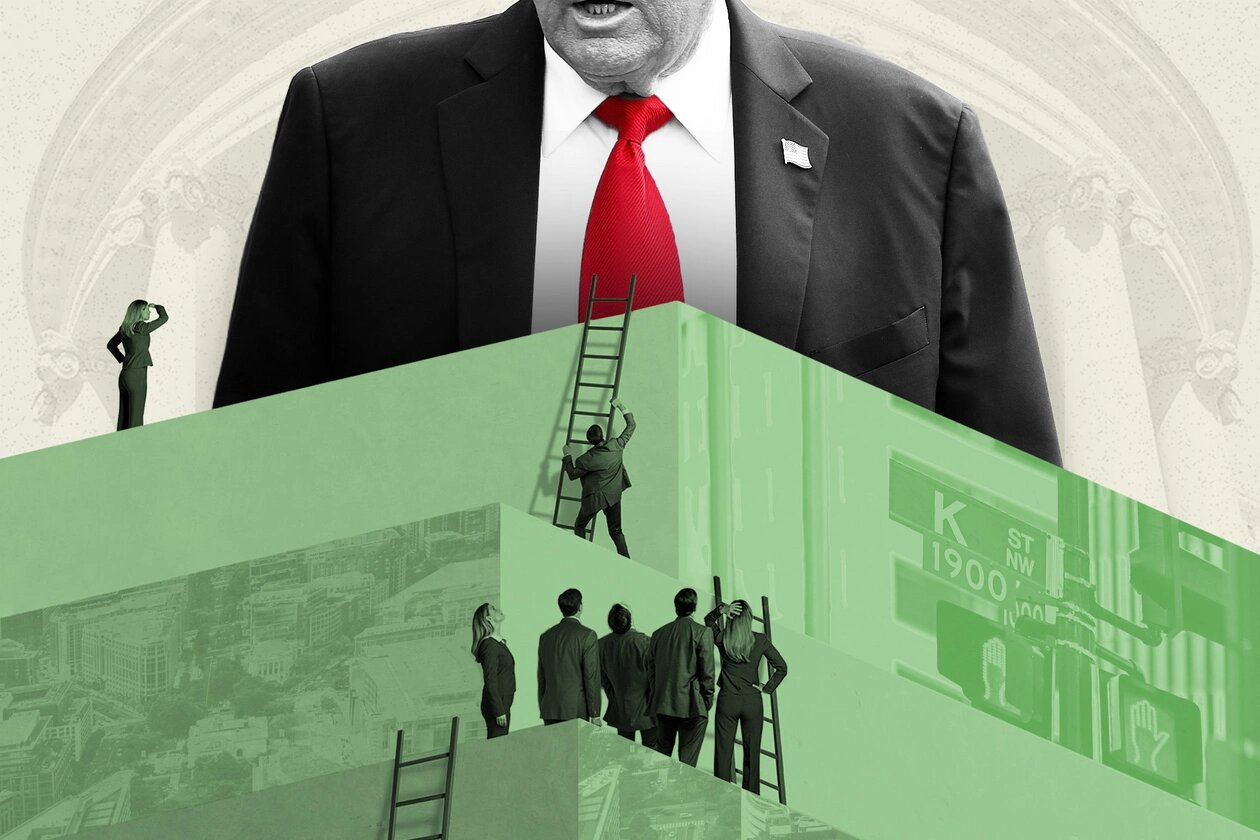

People in business suits climb ladders in an attempt to reach Trump.

Illustration by Jade Cuevas/POLITICO (source images via iStock)

By Brendan Bordelon, Amanda Chu and Caitlin Oprysko

10/19/2025 06:55 AM EDT

Intel Corp. looked like a winner in the Washington lobbying game at the start of 2025.

The federal government was set to funnel more than $10 billion to the American microchip giant, thanks to a long influence campaign by the company’s executives and hired Washington hands, who spent three painstaking years lobbying Congress, federal agencies and White House advisers.

Just a few months later, when a political controversy over the CEO’s links to Chinese companies put Intel’s deal with Washington in jeopardy, the whole drama was resolved in two weeks. And this time, the company’s path ran through just one person: President Donald Trump.

The sharp change in how Intel navigated Washington is being replicated across industries in Trump’s second term — by pharmaceutical companies cutting drug pricing deals with the White House, tech giants hoping to sell regulated equipment to China and energy firms that want looser environmental and permitting restrictions.

After decades of revolving-door culture, Washington is grappling with a new normal for how influence works in the capital. POLITICO spoke with several dozen lobbyists, industry officials and public relations professionals who revealed a transformation far more disruptive than the typical churn that comes with a new administration.

In Trump 2.0, American policy influence has shifted from its previous channels — agency officials, top lawmakers and staffers on key congressional committees — to a new reality where change comes suddenly from the top.

The president and a handful of lieutenants have seized full control over policies once considered the remit of Congress and experts at agencies, including hyperspecific issues like tariff rates, high-skilled visa fees and funding freezes. Trump’s gravitational pull has forced CEOs to act as their companies’ top lobbyists, plying the president with gifts and concessions to secure their policy priorities.

“The C-suites of America are now getting a first-hand opportunity to bang their heads against the wall,” said Niki Christoff, a tech consultant with stints at Salesforce and Google.

The new dynamic has transformed the business of Washington influence, shutting out many veteran lobbyists and excluding even longtime experts from the most important policy fights in Washington. With Congress and the agencies often sidelined, outside lobbying firms and in-house specialists — many with decades of policy experience and cross-party relationships — are declining in importance.

The example of Intel shows that direct personal lobbying can be strikingly effective — but also come at an enormous, and often unexpected, cost. After CEO Lip-Bu Tan was directly threatened by Trump in a social media post over his investments in Chinese companies, he flew to Washington, met personally with the president and agreed to hand the government nearly $10 billion in Intel stock to keep the company’s government subsidies alive — a measure not required by any law.

Similarly, the CEO of chipmaker Nvidia, Jensen Huang, built a personal relationship with Trump and ultimately won the right to sell chips to China — but only by giving the government 15 percent of its sales.

Their unusual concessions suggest that even CEOs with White House connections are struggling to adapt to a Trump-centric policy paradigm.

“In this administration, showing up is necessary but not always sufficient,” Christoff said.

‘A D.C. that doesn’t exist anymore’

Most lobbyists who spoke to POLITICO described the old levers of Washington influence and intelligence as increasingly broken, starting with Congress. The legislative branch is losing importance as Republicans — in charge of both chambers — take their cues from the White House to a degree that’s unprecedented in modern politics.

“Congress has basically taken itself out of the equation,” said Rich Gold, a Democrat who heads lobbying and law firm Holland & Knight’s public policy and regulation group. “There is a perception that Democrats have not fought back, and Republicans have basically ceded all their authority to the president.”

The same is true at federal agencies, which once operated more independently but are now closely responsive to the president himself.

From K Street’s point of view, there’s only one lever consistently worth pulling — and it sits in the Oval Office.

Lobbyists who can’t get clients in front of the president are struggling to adapt. Longtime lobbying heavyweights with extensive policy chops and Hill acumen — firms like Akin Gump and Holland & Knight — are facing greater competition from newer firms, like Ballard Partners, with direct lines to Trump and his aides.

Watch: The Conversation

Play Video

Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker and Jacqui Heinrich | The Conversation

And industry trade associations, once the crucial eyes and ears of member companies, are largely flying blind.

“The old school, establishment firms in D.C. don’t understand the new Washington,” said one lobbyist close to the administration, granted anonymity to candidly discuss the business landscape. “They are used to a D.C. that doesn’t exist anymore. It’s a different ball game from 10 years, or even five years ago.”

“After [Trump’s] first administration, they thought that the Trump movement would never come back,” said Carlos Trujillo, a former Trump administration official and president of lobbying firm Continental Strategy. “Now a lot of clients whom they’ve advised for years on their opinion of what’s happening … have lost faith and confidence in their understanding of government, and particularly Republican politics.”

The White House is aware that lobbyists are frustrated at being shut out of policy decisions — and one administration official called it a feature, not a bug, of Trump 2.0.

The official, granted anonymity to discuss sensitive relationships, said that if lobbyists or their clients are upset about a presidential proclamation, they can always work out details after the fact — though corporate leaders should be prepared to give Trump something in return.

Companies that can’t get their CEO into the Oval Office are searching frantically for new ways to capture White House attention. They’re increasingly turning to PR and advertising firms that can spread their message across television channels, social media accounts and podcasts popular with Trump and his lieutenants. Washington lobbying shops are consequently beefing up their PR and ad wings.

“Having a podcast ad on the Lex Fridman show, having a full-page ad in the New York Post, having a digital ad campaign on Facebook surrounding people close to the president who aren’t in the administration — that is more like inception than direct advocacy,” said Christoff. “And it’s a new paradigm for Washington influence.”

A president who intervenes

The opinions of presidents and White House advisers have always been important to federal policymaking, and to anyone trying to influence it. But presidential power was historically felt at 30,000 feet, leaving experts in government and industry to hash out thorny details.

Most Read

Hayden Padgett, chair of Young Republicans, speaks during the Republican National Convention.

‘Meanest people I have ever met’: Chat leak resurfaces internal fights among Young Republicans

Trump struggles to crack tariff piggy bank

IRS files tax lien against Jim Justice

Speaker Johnson defends Trump’s decision to commute Santos sentencing

The king of the shutdown

James Thurber, professor emeritus at American University who studies lobbying, said Trump’s approach is fundamentally different.

“He’s micro-managing phenomenally in terms of a variety of issues,” said Thurber, calling it a drastic departure.

“The last thing you did was go to a president and try to get things done, because it didn’t really help,” said Thurber. “You had to figure out the network of players. You generally did the lobbying at the middle level — in the bureaucracy, and at the committee level and subcommittee level on the Hill.”

With lobbyists now ignoring expert staff and devaluing policy knowledge in favor of White House access, Thurber worried Washington will land on policies that are divorced from reality and riven with presidential quid pro quos.

“In a democracy, you need knowledge, you need expertise, you need to understand what the consequences are of particular policies, and you need to be involved in deliberation,” said Thurber. “All of those things are being lost when you go directly to a president who shoots from the hip and believes in reciprocity.”

In a statement, Trump administration spokesperson Kush Desai said circumventing lobbyists was part of the point.

The American people “firmly rejected The Swamp’s business-as-usual politics and policymaking when they resoundingly re-elected President Trump,” he said. “The only special interest that is influencing President Trump and his Administration’s decision-making is the best interest of the American people.”

Trade associations sidelined

On the night of Friday, Sept. 19, officials at trade groups representing two of America’s most powerful industries opened their phones and found themselves in shock.

Trump had just declared that the U.S. would be slapping a $100,000 fee on visas for high-skilled workers entering the country — upending a crucial talent pipeline for the technology and health care industries.

The proclamation arrived with none of the usual warnings that accompany policy changes in Washington — no notice of proposed rulemaking, no request for industry feedback, no heads-up to Capitol Hill. Even the most connected lobbyists and industry representatives were left searching for answers and groping for a coherent response.

Similarly, when Trump announced wide-ranging tariffs earlier this year, the trade associations were as surprised as anyone by the scale, scope and specifics. Industry groups and lobbyists struggled to even understand the changes, much less influence them.

That’s a sharp change from the Washington norm, where trade associations have long wielded influence — and also been companies’ eyes and ears in the capital. They’ve historically served as crucial intermediaries between policymakers and the companies they regulate, as well as an early-warning system on coming policy shifts.

Now, instead of seeking expert feedback or soliciting approval, one representative from a top tech trade group said the White House tends to ignore them in most cases.

“The administration doesn’t like to reach out to associations on any matter, unless it’s something where they have a very specific interest in terms of advertising what they’re trying to do,” said the representative, granted anonymity to discuss sensitive talks.

The rise of the CEO-lobbyist

With lobbyists and trade groups struggling to gain access, many CEOs have taken matters into their own hands. Particularly in the tech sector, they’ve become their companies’ most important lobbyists — Nvidia’s Huang, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, Apple CEO Tim Cook and others now regularly visit the White House, even traveling with Trump on a recent state visit to the United Kingdom.

CEO charm offensives are often aimed at securing an exemption to whatever new policy Trump has imposed — most often tariffs, with Nvidia and Apple managing to finagle carve-outs for their products.

“In the first Trump administration, you could go to the secretary of commerce and get an exemption to a tariff,” said Christoff. “You now cannot get an exemption to a tariff without going directly to President Trump.”

But even the tech titans have at times struggled to leverage their direct lines to Trump. Christoff pointed to last month’s high-skilled visa blowup, juxtaposing it against a White House dinner where tech CEOs fawned over the president just days before his H-1B proclamation.

“This was a meeting of tech billionaires being very deferential to President Trump,” said Christoff. “And all it got them was a talent tax headache.”

A new K Street takes shape

Despite the upheaval on K Street, Washington’s lobbying sector is on track to earn more money than in any year since 2010, adjusted for inflation — driven by corporations’ mix of enthusiasm and concern about what Trump is doing.

That revenue is flowing away from established firms with policy expertise and robust networks of cross-party contacts, and toward a handful of rising firms able to open the Oval Office door.

Ballard Partners is one of those firms. Its Trump-friendly lobbyists registered more than 160 new clients so far this year, outpacing second-place Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck by 40 percent. White-shoe firms like Brownstein, Akin Gump and Holland & Knight still tend to bring in the most money — but newer Trump-linked firms are challenging them and racking up clients. Among them are Continental Strategy, led by former Trump official Trujillo, and Miller Strategies, led by veteran GOP lobbyist Jeff Miller.

“Many of the people who are really powerful in the lobbying world today are the Trumpers and the lobbyists that are closely connected to Trump,” said Seth Bloom, a former Democratic congressional aide who’s now a top Washington lobbyist. “We saw it a little bit in Trump’s first term, but not to the same extent.”

“It’s Darwinism,” said Sam Geduldig, managing partner at Republican lobbying firm CGCN. “Why would you pay expensive lobbying fees to a firm that can’t have honest conversations with the people in charge?”

Companies that can’t get their leaders or lobbyists into the Oval Office are increasingly pouring resources into PR and advertising firms, often with an eye to influencing right-wing personalities on social media.

The Trump administration is heavily influenced by far-right voices on the internet — people like Laura Loomer, a MAGA influencer whose posts on X have a direct impact on White House policy. Among other things, Loomer has forced out federal officials and pushed Trump on more firings. She was allegedly behind Trump’s recent call for Microsoft to fire its head of global affairs, former Biden administration official Lisa Monaco.

“The traditional conservative voices that may have appealed to previous GOP administrations don’t always resonate in the age of Trump,” said Jeffrey Kimbell, president of Jeffrey J. Kimbell & Associates, a health care lobbying powerhouse. “Our industry must get creative about the voices we choose to echo our messaging.”

Top Trump officials, particularly those with health and tech policy portfolios, are also voracious consumers of specific podcasts and Substacks — ripe targets for digital ad campaigns meant to incept ideas directly into the White House. The new vector of attack has prompted D.C. firms to retool; Brownstein, for example, launched its public affairs practice in June.

“There are opinions being formed and political constituencies being activated online more than they are offline right now,” said Ballard partner Justin Sayfie.

The natural lobbying order could always reassert itself in Washington. Legacy lobbying firms point out that partisan lobbying surges in any new administration — George W. Bush brought a Texas flavor to K Street in the early 2000s, and Barack Obama oversaw the rise of Democrat-leaning shops. And they say established firms have survived rough political cycles before.

Lobbyists for more traditional firms also question whether clients of Trump-friendly shops are getting their money’s worth.

“You only have so much fuel in the tank with the president or the West Wing,” said a founder of a major Washington lobbying shop, granted anonymity to speak freely. “Perception may not meet reality on what their clients’ expectations are.”

Many legacy lobbying firms are staying the course. They’re keeping their political contacts broad and their policy expertise sharp, confident that Washington will revert to type within the next few elections.

“It could all change in a year, change in two years,” said Kate Bennett, vice president of advisory and external affairs at lobbying shop Invariant. “If you’re day trading on Washington, it’s a risky stock.”