Mice, “nan’s bathrooms,” carpets duct-taped together — and terrible phone signal.

Is there a worse place to run a country from than 10 Downing Street?

The world knows it as No. 10, but the real insiders call it “the house.”

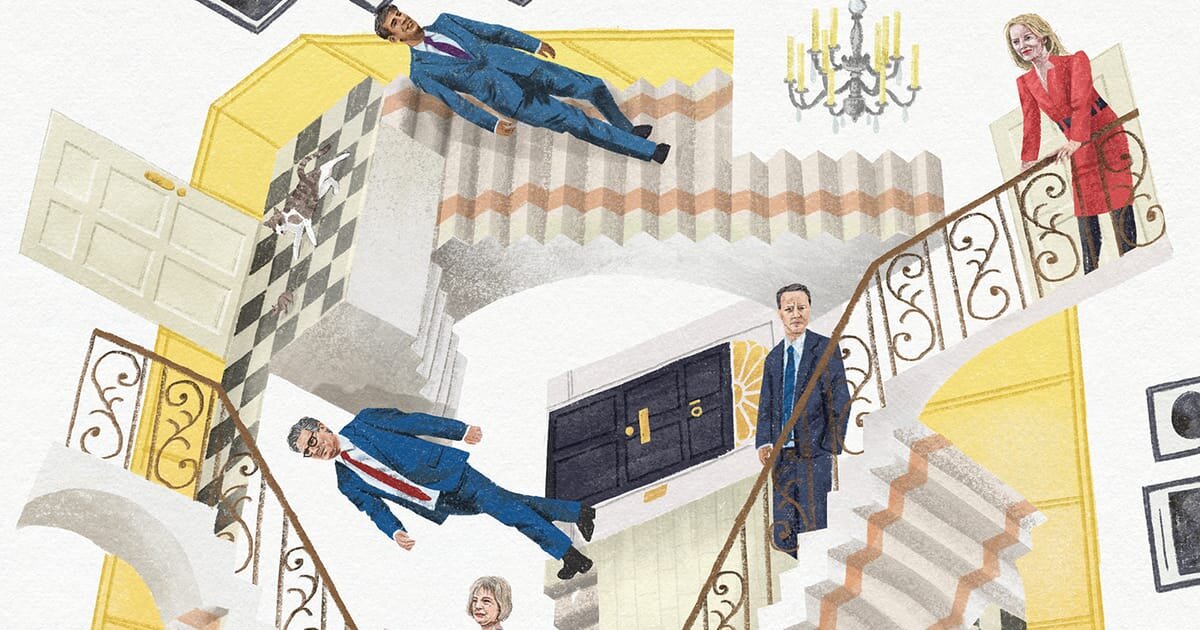

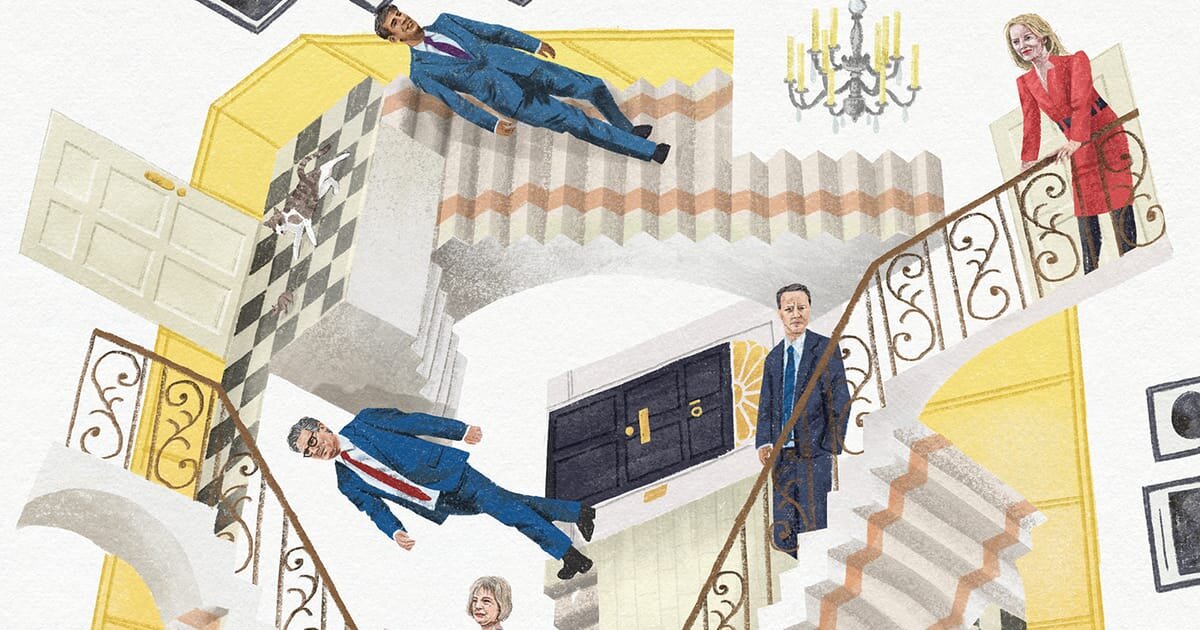

Walking through Downing Street’s steel black door invokes a thrill in even the most seasoned cynic. But behind it, Britain is run from a maze of poky rooms in three seventeenth-century terraced homes knocked together.

The building sprawls backwards over four floors and a basement with mice, net curtains, toilets like a grandmother’s, cranky heating and patchy phone signal. It is the U.K. prime minister’s office, events space and home in one, and has been that way (with a few gaps) since the 1700s.

These things all seem trivial, but they invite a serious question. For all its history, does the building itself undermine the work of the state?

“Those tiny rooms just encourage silo thinking and infighting,” said a long-serving Cabinet minister under previous Conservative administrations. An ex-No. 10 official under its current occupant, Keir Starmer, was blunter: “It’s mad that a G7 country is run from a Georgian townhouse.”

“The building is the perfect metaphor for the state of Britain,” added a former No. 10 official under Rishi Sunak. “It’s all built on top of itself, full of sticking plasters … There are doors that go to nowhere.”

The consequences are real. This week No. 10 was compared to a “bunker” — not for the first time — after chaotic anonymous briefings that Starmer could face a coup.

POLITICO dived into the building’s strange world to find out how PMs over the years have coped — and whether it is making Starmer’s already sputtering premiership even harder.

This article and a Westminster Insider podcast are drawn on reflections from more than 25 current and former officials and politicians who have worked there, most granted anonymity to speak freely.

Britain’s prime minister is an open-plan man. Before entering government he preferred Labour’s modern, bare-brick HQ across the River Thames to his fusty offices in parliament. He was a “leaner” who would stand over colleagues’ desks, said the first ex-official quoted above.

While Starmer is seldom able to visit Labour HQ now, he spent three days there in September writing his speech to the party conference, one of his better-received moments as PM.

Starmer is the latest in a line of PMs who have grappled with the house’s strange geography. “I don’t think any prime minister has actually liked working from there,” said one long-serving former No. 10 official. “I think most of them just end up settling for it.”

One senior ally of Starmer has been heard describing Larry the Cat, who has been No. 10’s “chief mouser” since 2011, as a metaphor for the British state — old, lazy, too pampered to do the job he was hired for (catching mice), yet unsackable due to a sense of fondness and tradition.

Some are even tempted to link the errors and scandals of Starmer’s first 16 months — including endless complaints about poor communication and a lack of direction — to the frustrations of the old house. The layout made the PM’s problems “immeasurably” worse, argued the first ex-official quoted above. “It’s a nightmare. Departmental teams often communicating with different bits of No. 10 with different steers as a result.”

It is easy for staff to become siloed, said a third ex-No. 10 official under Starmer, because pivotal chats happen in small rooms or a corridor. The PM’s chief of staff Morgan McSweeney is also said to be frustrated by No. 10.

Few would be so charitable — or brave — as to truly blame the building for Starmer’s ills. “In my experience of governments that are doing either well or badly, I’m not sure the layout of Downing Street is the dominant factor in their successes or failures,” said Simon Case, who was cabinet secretary (No. 10’s most senior civil servant) from 2020 until last year.

But most people agree: it doesn’t make Starmer’s job any easier.

At war with a building

It’s the little things.

Liz Truss would start most mornings by exercising with her most senior aides in Downing Street’s walled garden or at nearby Lambeth Palace. When the team got back to No. 10 they hit a problem.

Apart from in the apartments reserved for the PM and chancellor, Downing Street has only two showers, both on the upper floors. One is used by staff, while the other is semi-reserved for the “custodians” who look after the building, said a second long-serving ex-official.

“They’re not normal office showers,” they added. “It’s like using your Nan’s bathroom.”

A former aide to Truss recalled: “All the senior staff couldn’t start work because we all smelled disgusting and were sweaty. We’d go to the top floor where there was, like, one shower for the staff, and we’d all be literally queuing up to use it. And someone would already be in there, like a police officer changing shift.”

Then there’s the archaic heating, always too hot or cold. One former aide under Boris Johnson recalled a high-profile visit to No. 10 in December 2019: “The heating had been cranked right up, and Donald Trump was there, and we did a quick meeting with him and Boris. [Trump] was sweating, and his orange makeup was just kind of dripping down his face. That was disgusting.”

When summer rolls around, staff covet the winches they need to open most windows, as if they are on a boat. But opening them creates a new problem — the sound of marching bands rehearsing on Horse Guards Parade, just over the wall, for the king’s birthday parade. “It’s weeks and weeks of rehearsing and noise,” recalled one ex-official under David Cameron. “You would have to move rooms [to have a phone call].”

That’s if you can get reception, of course. “The phone signal is just atrocious in there,” said the former Truss aide quoted above. “It’s an absolute fucking nightmare.”

Then there is the tech. Ministers who have spanned both No. 10 and the Cabinet Office arrived only to discover that the two groups of officials use different systems. Some need multiple work phones.

Sometimes there is slapstick reminiscent of Scooby-Doo. The former Johnson aide quoted above recalled how two people would be employed to fetch the then-PM — not known for his timekeeping skills — from his flat, reached by both an elevator and a staircase. One aide would climb the staircase while the other waited at the bottom of the lift shaft to avoid Johnson slipping through their grasp.

As if in a magic castle, rooms can vanish and reappear in new guises. Various aides recalled either a room or suite on the third floor that had been through so many uses that they could not all agree on what it was for. It probably housed David Cameron’s nanny, was converted into a staff meeting room under Theresa May, then housed Johnson’s mother-in law (“because Boris didn’t want her staying in the flat,” quipped one ex-official), then became a meeting room again. One ex-Johnson aide, however, swore it was a mini-gym.

Parking spaces were no easier to assign, as Truss’ personal trainer — who had a car — discovered, said the ex-Truss aide quoted above. “By the time we got the car park sorted, Liz had resigned,” they said.

Then there is just the general atmosphere of an old house — no matter how pristine the first floor state rooms (which were refurbished under Margaret Thatcher). “It’s a bit like a three-star Bournemouth hotel,” recalled Jim Clay, who designed a film set aping No. 10 for the 2003 film Love Actually.

“It’s a bit gross, the building,” recalled the former Johnson aide quoted above. “It’s old and crumbly.” Sometimes a “stench” would emit from a toilet, they added: “Most people, especially Americans, would come in and be a bit taken aback by how shabby it is. The curtains might be a bit frayed, or there’s a rip in the rug, which is temporarily repaired by putting some duct tape on it, but it never gets properly fixed.”

The ex-aide recalled once walking past a prawn on the floor of No. 10’s famous yellow staircase, which is lined with portraits of past PMs. “It was there for, like, a week.”

Proximity is everything

Downing Street has only 250 to 300 staff — including caterers, security and custodians — and the true nexus of power is far smaller.

Starmer’s 8.45 a.m. meeting in the Cabinet room features only a handful of key figures, according to a person with knowledge of it: they tend to be the PM, McSweeney, Chief Secretary Darren Jones, deputy chiefs of staff Vidhya Alakeson and Jill Cuthbertson, Chief Whip Jonathan Reynolds, Director of Communications Tim Allan and Principal Private Secretary Dan York-Smith.

Aides then decamp without the PM to a wider meeting at 9.15 a.m. with other aides such as Head of the Policy Unit Harvey Redgrave, Political Director Amy Richards and the PM’s private office staff.

Proximity to power is king.

Like most prime ministers since Tony Blair, Starmer does much of his work from a room dubbed “the den” next to the Cabinet room on the ground floor.

People who have been say Starmer’s outer office has around eight desks, staffed by McSweeney, Alakeson, Cuthbertson, York-Smith and other civil servants in his private office.

Despite his powerful role in foreign policy, National Security Adviser Jonathan Powell is one staircase away in a room next to other No. 10 private secretaries. Jones is next door to them. Digital and strategy teams are in the basement, near the canteen and looking out on the walled garden; the policy unit is way up on the second floor.

This layout — used by most PMs since Tony Blair — means opportunistic staffers will linger around the outer office on the ground floor, hoping to engineer a “chance” meeting with the PM or his aides. This is easier under some gatekeepers than others. In Boris Johnson’s day, said the ex-aide quoted above, “sometimes none of them would be there and you could just walk straight in.”

Thérèse Coffey, a former Conservative Cabinet minister who was briefly Deputy PM under Liz Truss, said: “I actually think No. 10 is an interesting building, and it can work. But the real power is who gets to give the last note in the box, and who has the opportunity for the brush-by conversation.”

So perhaps it is no surprise that Starmer — who likes order and process — often gravitates to the first-floor study which Margaret Thatcher used as her office in the 1980s. A third ex-official under Starmer said he uses it for “reflective” reading away from the “hustle and bustle of the ground floor.” The current PM famously took down a portrait of Thatcher in the study because he disliked “people staring down at me”.

Case said: “I think probably on various occasions he complained about noise [downstairs] — which, actually, I think a lot of his predecessors have complained about.”

For those without proximity to the PM, No. 10 can be frustrating — and few suffer a worse fate than the policy unit. Though it is only on the second floor, some jokingly refer to it as the “attic.” That level has its own toilet, depriving staffers of the chance to linger past the lobby (No. 10’s power center) to see who is visiting. Policy staff are divided into multiple rooms. A fourth former No. 10 official under Starmer said: “They have fireplaces. They feel like bedrooms that have had desks shoved in them.”

“It’s certainly been a source of some frustration to policy unit people,” agreed Case. He added, however, that Tony Blair’s policy unit was immensely powerful — “and they didn’t have any problem making it work from the second floor.”

‘They sniff out power’

The biggest issue is the lack of space. While Downing Street sprawls into extensions and other buildings, much of it — voids, stairs, corridors — can’t be used for desks. The chancellor’s area in No. 11 sits in the middle of the complex, dividing the main prime ministerial offices into two.

This has led to endless stories about the seating plan. Powell, a former aide to Blair in No. 10 who helped clinch the Belfast peace agreement in 1998, wrote in his diary that negotiating three offices in No. 10 was “harder than trying to sort out Northern Ireland.”

Starmer’s first chief of staff, Sue Gray, was accused of moving McSweeney’s desk further away from the PM last year. Case said he did not recognize that story but added generally: “I think factionalism is an issue inside the prime minister’s team. Location can play a part in that.”

Canny aides quickly learn how to use the geography to their advantage. “The building is great,” argued John McTernan, Blair’s former political secretary. “The people who normally complain about the building are staff who are not close enough. When I first was there with [Blair’s strategy aide] Matthew Taylor, we shared an office down a corridor by the toilets, because it was the closest we could get to Tony.”

But they can still be left at a loss. The former Johnson aide quoted above said the layout was “massively unhelpful” for running the country and “not fit for purpose.” They added: “If I needed the policy unit, I wouldn’t be able to find them. I would ask them to come down and meet me in the lobby … which is pathetic, but that is an illustration of how messed up it is there.”

Few have mastered No. 10’s geography like its old guard of civil servants — many of whom have seen a procession of political occupants come and go.

“They sniff out power, line up behind it and engineer the building in a way that works for them,” said the fourth ex-Starmer official quoted above. A former mid-ranking political appointee under Rishi Sunak said: “I felt like a parasite that [they] wanted to remove.”

It’s not always this simple. It is terribly convenient for a chief of staff — who has presided over the seating plan — to shrug and point to faceless civil servants when they are challenged.

But the ex-Truss official quoted above said: “[The civil servants] basically end up shunting most political appointees out to other parts of the building. It all gets so silly. We came into Downing Street and every single desk had, like, a name card on it. I’ve never known a building where ‘where you sit’ becomes so important.”

The house always wins

Some prime ministers have tried to defeat the house’s geography. None have yet succeeded.

Powell urged Blair in the late 1990s to move operations into the 1980s-built Queen Elizabeth II conference center and turn No. 10 into a museum. He was unsuccessful.

Gordon Brown abandoned the “den” and moved into the largest office, a wood-panelled room on the ground floor in No. 12. Chucking out the press officers that had resided there, he created a “horseshoe” where he could talk to senior aides more directly — whether they liked it or not.

“I’m not sure those who worked for him always appreciated the fact that he was a presence over us all,” recalled one ex-official under Brown, tactfully. The ex-PM was well-known for his temper.

This war room did not prevent Labour crashing to defeat in the 2010 election — giving way to Cameron, who resumed life in the den. Case said: “It’s hard to look back on that and say that was a roaring success. Open plan working isn’t the be all and end all of government working well.”

Liz Truss — who has made her disdain for the civil service “Blob” clear — tried to do things differently in her 49-day tenure. She was the first and only PM since John Major in the mid-1990s to work from the Cabinet room, which normally sits empty when not hosting meetings.

This was perhaps more successful than her other changes. Truss bruised civil servants’ egos by moving the entire policy unit out of No. 10 and into the Cabinet Office. “They were literally told with a couple of hours’ notice to pack up and go, which infuriated them, understandably,” recalled the second long-serving ex-official quoted above.

Like Brown before her, Truss also booted the press office out of its prime spot in No. 12 — but to restore it to its old purpose of hosting the chief whip. It did not work.

Truss was going back to “the days when really No. 12 was the chief whip’s absolute fiefdom,” recalled Coffey — who, as her deputy PM, was meant to be based in the space, too. “What she did want to do is bring together the political side of government.”

But the chief whip and Coffey (who was simultaneously the health secretary) both had other bases. The second long-serving ex-official said: “In practice it was basically empty. One day it was basically in pitch darkness because there were only two people in the entire room, they hadn’t moved for a while, and so the lights [which ran on automatic timers] had gone off.”

Coffey said: “I wasn’t there all the time, I think is a good way of putting it.”

Rishi Sunak also grappled with downsizing over the course of a few months from a job as chancellor, where he had a Downing Street residence and the enormous Treasury round the corner from No. 10. “He found it deeply frustrating that he had lost so much resource” and used to call Treasury officials directly for advice, recalled one ex-official who worked under him.

There are no secrets in this house

The most draining element for prime ministers is the claustrophobia.

Unlike nearby Buckingham Palace, which has the largest private garden in London (the U.S. ambassador’s residence in Regent’s Park claims second place), the PM has only a small outside area. And it is overlooked by his own staff — as Johnson discovered when an official “papped” him attending a gathering in the garden during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Friends and family wander through the heart of government offices, the front door is watched at all times, and photographers are often trained on the back gate. Starmer’s children are never named or pictured, but this is largely due to British press regulation rules and a mutual understanding with the PM, who is fiercely protective of his family’s privacy.

Sometimes the mix of public and private is comical. McTernan recalled: “When we had trade unionists at drinks, I always made sure they knew there was a bathroom — then an avocado suite — which was Margaret Thatcher’s toilet for her study, and they all wanted to use it. They all wanted to have a shit in Thatcher’s toilet.”

Sometimes it was also — whisper it — fun. The larger of the two private apartments is bigger than many people realise. Two former Downing Street officials described it as having around six bedrooms and being split between the third and fourth floors, with a chandelier in the entrance.

Ex-Chancellor Jeremy Hunt (who Sunak let use the bigger flat due to the size of his family) once hosted a party whose attendees included the British-Iranian former prisoner Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe and the Classic FM presenters Alexander Armstrong and Myleene Klass, because Hunt was a fan of the radio station. At one point, Armstrong sang while Hunt stood conducting on a chair.

But this lifestyle has also perturbed successive PMs — and their partners. Johnson’s wife Carrie gave birth to their first child together while he was PM. The lack of privacy “bothered Carrie, and therefore it bothered him,” said the ex-aide quoted above.

When the Johnsons infamously had the flat renovated at great cost, “you could hear the banging day and night,” said the second long-serving ex-official quoted above.

And all that was without “Partygate,” the revelations of lockdown-busting gatherings in No. 10 — a place hardly set up for social distancing — which helped turf Johnson from office. Johnson received one fixed penalty notice from police, but claimed ignorance of many other events.

This prompted incredulity from those who pointed out Downing Street was his home. But the sprawling layout “might have had something to do with it,” said Case (whose own avoidance of a Partygate fine angered many civil servants). “It probably made it possible for some things to be going on in a bit of the building that other people didn’t know about.”

House proud

To many who have passed through No. 10’s black door, all these gripes miss the point.

The entire appeal of the house is its history. Downing Street’s British quirks give the premiership character — and stop a slide into faceless bureaucracy.

“The symbolic power is enormous,” said the former Sunak appointee quoted above. “I don’t think it’s worth discounting that.”

Downing Street’s quaint set-up may look provincial compared to many European countries, the White House, a U.S. senator’s office, or most private firms. But Britain does not have a president, and the role of the PM — beyond executive functions such as the nuclear codes — is very different.

No. 10 is also meant to be the inspiration, while government departments do the perspiration. “We tend to think of decision-making in terms of, like, flow charts and organic brands and things like that,” said an ex-official under Theresa May. “Quite a lot of the time it’s a bit more organic.”

McTernan said: “I think people sweat the issue of running the country from Downing Street because they kind of think it’s a machine, or a factory, or it needs a central office.” No, he argued: “You’re the brain.”

No. 10 will always be prone to chaos, too. It is a clearing house that has crises dumped at its door. “It only deals with difficult shit,” said a third long-serving ex-official. “It only attracts things where either the prime minister is particularly interested … or where there’s disagreement across government, or it needs a bit of coordination.”

There are complaints across Whitehall that No. 10 is siloed and struggling under Starmer.

Its success or failure, argue many, will ultimately come down to the PM’s interpersonal relationships — Starmer has churned through a rolling cast of senior officials in his first 16 months — and their leadership, or lack of it.

“In my experience, the Whitehall machine will respond to the signals and the political direction from a leader who knows what they want to do,” said the ex-official under Brown quoted above. “Tony Blair, Gordon Brown and I suspect David Cameron had a sense of what it was they wanted to do. And therefore the wider Whitehall machinery responded to that.”

“This is about the skill of being a successful prime minister,” Case added. “Each of them does have their own way and their own style. But at the heart of the story is usually that they have a clear direction or a clear vision, that they’re good at taking decisions, and that they are really good at getting the most out of the people around them.”

McTernan put it the most bluntly. Botched cuts to welfare under Starmer were a “failure of values, not a failure of location,” he said. “The problem with any government is, if you don’t know what you want to do, how are you going to know how to do it?

“And then you blame your tools. The house is a tool. If you know what you’re going to do, then you know how to use it.”