In a rare move, the judge ordered prosecutors to hand over records of the grand jury proceeding to the former FBI director’s lawyers.

A federal magistrate judge says “government misconduct” may have tainted the criminal case against former FBI Director James Comey, describing a cascade of apparent errors by lead prosecutor Lindsey Halligan.

The magistrate judge, William Fitzpatrick, ordered prosecutors Monday to quickly turn over records of secret grand jury proceedings to defense attorneys as they seek to dismiss the false-statement and obstruction-of-Congress charges pending against Comey in federal court in Alexandria, Virginia.

“The Court recognizes this is an extraordinary remedy,” Fitzpatrick wrote in a 24-page opinion, “but given the factually based challenges the defense has raised to the government’s conduct and the prospect that government misconduct may have tainted the grand jury proceedings, disclosure of grand jury materials under these unique circumstances is necessary.”

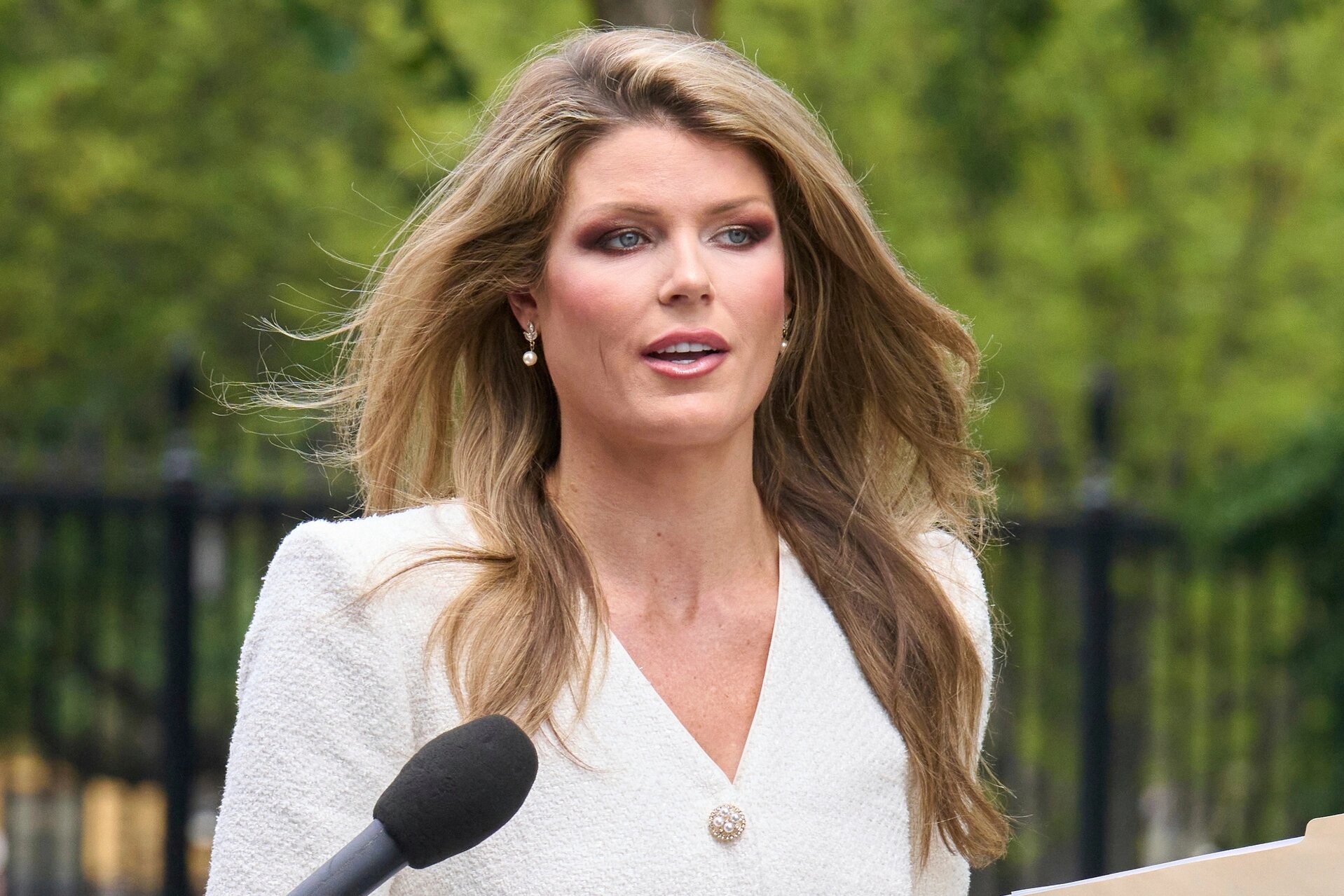

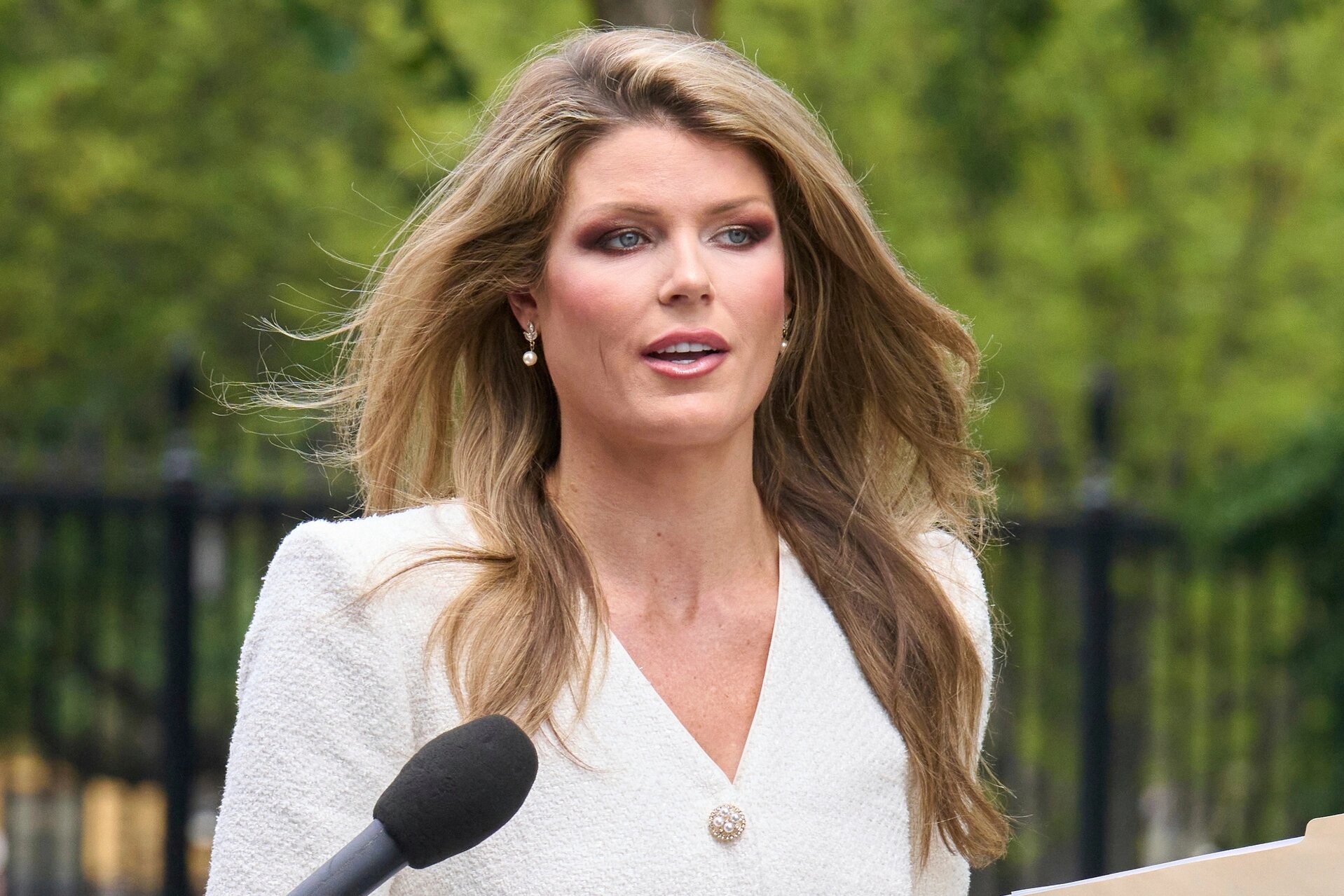

Fitzpatrick’s decision came after he personally reviewed records of the grand jury proceedings that led to Comey’s Sept. 25 indictment on charges that he lied to Congress in 2020. The indictment was signed by Halligan, President Donald Trump’s handpicked prosecutor, who was installed by Attorney General Pam Bondi when other prosecutors resisted bringing the case against Comey.

The magistrate judge’s assessment adds to the mounting possibility that Comey’s case will be dismissed before it goes to trial. In addition to the procedural flaws Fitzpatrick said appeared to occur, Halligan is facing a challenge to the validity of her appointment altogether and could be disqualified from the case.

Fitzpatrick raised sharp doubts about an account of the grand jury proceedings provided by the Justice Department and whether it had turned over all records of the interactions between Halligan and the grand jurors. He noted that Halligan had claimed she had her last contact with the grand jury at 4:28 p.m. that day, while the jurors were deliberating. But he also noted that the grand jury initially rejected one of the counts against Comey, leading prosecutors to prepare a new indictment that Halligan ultimately signed. Yet nothing in the record reflects the grand jury’s initial decision or consideration of the second indictment, Fitzpatrick said.

“The short time span between the moment the prosecutor learned that the grand jury rejected one count in the original indictment and the time the prosecutor appeared in court to return the second indictment could not have been sufficient to draft the second indictment, sign the second indictment, present it to the grand jury, provide legal instructions to the grand jury, and give them an opportunity to deliberate and render a decision on the new indictment,” Fitzpatrick wrote.

Fitzpatrick also said Halligan, who had never prosecuted a case prior to Comey’s, appeared to make two “fundamental misstatements of law” to the grand jury that could jeopardize the indictment altogether.

He said Halligan, facing tough questions from grand jurors, appeared to suggest Comey might have to testify at trial to explain his innocence, an improper characterization of the government’s burden to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Fitzpatrick also said Halligan appeared to improperly suggest grand jurors could assume the government had more evidence against Comey than what it presented to them.

“The record points to a disturbing pattern of profound investigative missteps, missteps that led an FBI agent and a prosecutor to potentially undermine the integrity of the grand jury proceeding,” he wrote.

U.S. District Judge Michael Nachmanoff, the Biden appointee overseeing the case against Comey, assigned Fitzpatrick last month to address some issues related to possible violations of attorney-client privilege. At a hearing earlier this month, Fitzpatrick ordered prosecutors to turn over all the grand jury transcripts to the defense, but Nachmanoff told the magistrate judge to reconsider after prosecutors objected.

Prosecutors could also appeal Fitzpatrick’s latest decision to Nachmanoff. Spokespeople for Halligan and the Justice Department declined to comment.

Fitzpatrick also expressed particular concern that Halligan’s presentation relied entirely on the testimony of a single FBI agent who may have reviewed material subject to Comey’s attorney-client privilege with longtime associate Daniel Richman, a Columbia law professor who also served as an official adviser to the FBI director. The FBI agent was made aware that he may have inadvertently reviewed the material improperly, Fitzpatrick said, but still “proceeded into the grand jury undeterred and testified in support of the pending indictment.”

“The government’s decision to allow an agent who was exposed to potentially privileged information to testify before a grand jury is highly irregular and a radical departure from past DOJ practice,” the magistrate judge wrote.

Fitzpatrick also said the agent may have reviewed materials that went beyond those the government had been authorized to examine.

“The government appears to have conflated its obligation to protect privileged information – an obligation it approached casually at best in this case – with its duty to seize only those materials authorized by the Court,” wrote the magistrate judge, who slammed the government for its “cavalier attitude” toward the issue.

Prosecutors routinely seek a new search warrant when they want to use old evidence in a new investigation, but they did not do so in this instance, the judge said. He called the decision inexplicable but also suggested that it stemmed from an unrelenting drive to beat a statute-of-limitations deadline to indict Comey that was set to run out last month.

Prosecutors have argued that in the event the indictment against Comey is dismissed a federal law effectively extends the statute of limitations for six months after that ruling or the resolution of any appeal. Comey’s lawyers say the extension would not apply in these circumstances.