Top contenders to lead the Federal Reserve under Trump are lining up around a policy that doesn’t seem Trump-like.

President Donald Trump has loudly and persistently railed against Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, with an eye toward next year when he can pick a new Fed chief more aligned with his own views.

But in the race to replace Powell, much of the conversation has focused on something that doesn’t feel particularly Trump-y: limiting the size of the Fed’s financial holdings.

Trump, famously, loves low rates. He has said repeatedly that he wants lower mortgage rates and to reduce the amount of interest that the federal government pays on its debt.

And yet, momentum seems to be building toward curbing a Fed tool that is aimed at doing exactly that.

The reason why the U.S. central bank’s holdings are so large — well in excess of $6 trillion — is that the institution acted during the past couple of crises to stimulate the economy beyond just lowering short-term interest rates to zero. To drive down longer-term rates, which are more important to borrowers looking to finance the purchase of a home or a car, the Fed also grew its balance sheet by snapping up trillions of dollars in U.S. government debt and mortgage-backed securities.

Now, Trump allies are debating whether the Fed should do less in the next recession.

It poses a potentially revealing question as the president weighs his choice to head the central bank: Does he want to reduce the Fed’s influence over markets, or does he want to use that influence to further his desire for the lowest rates possible?

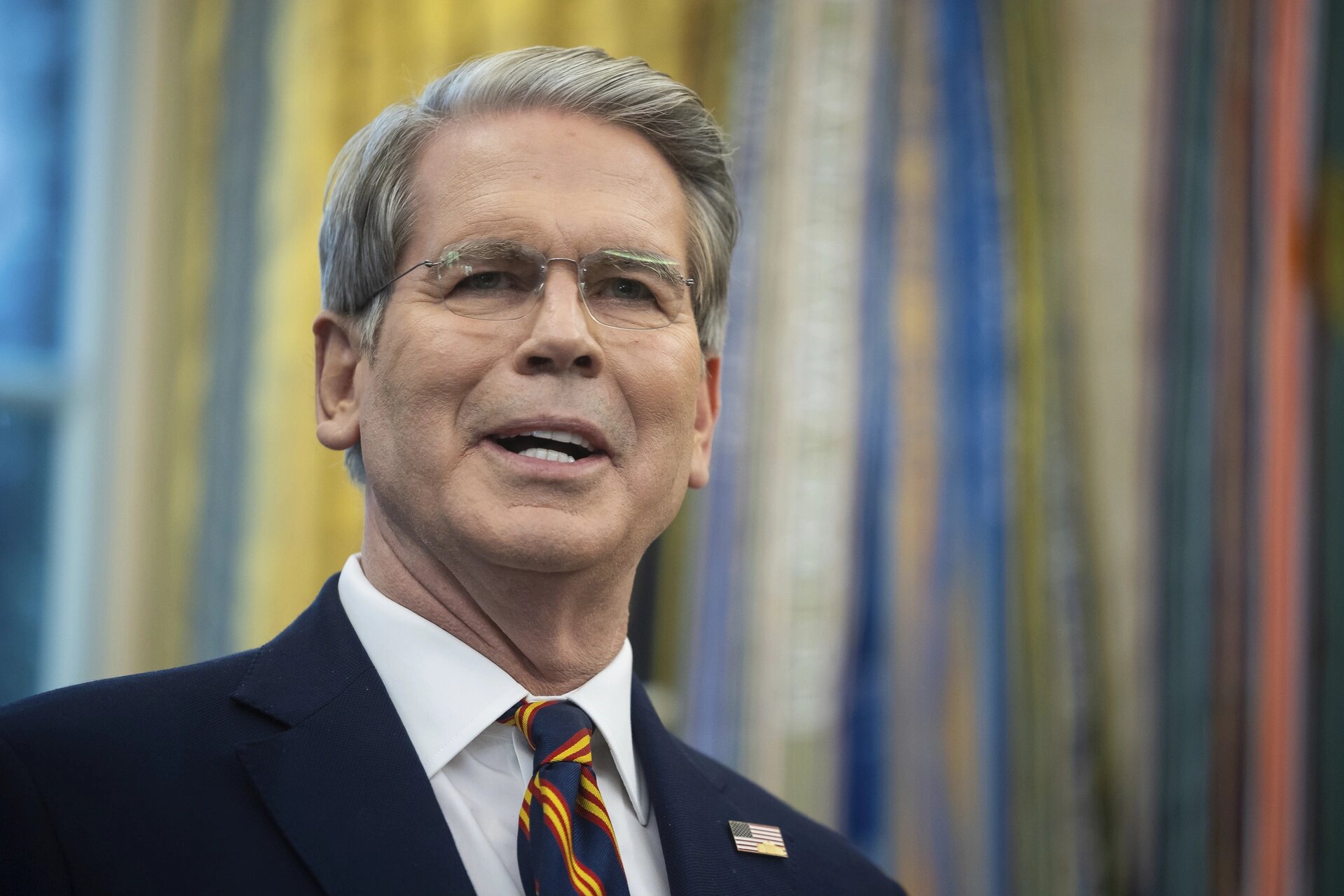

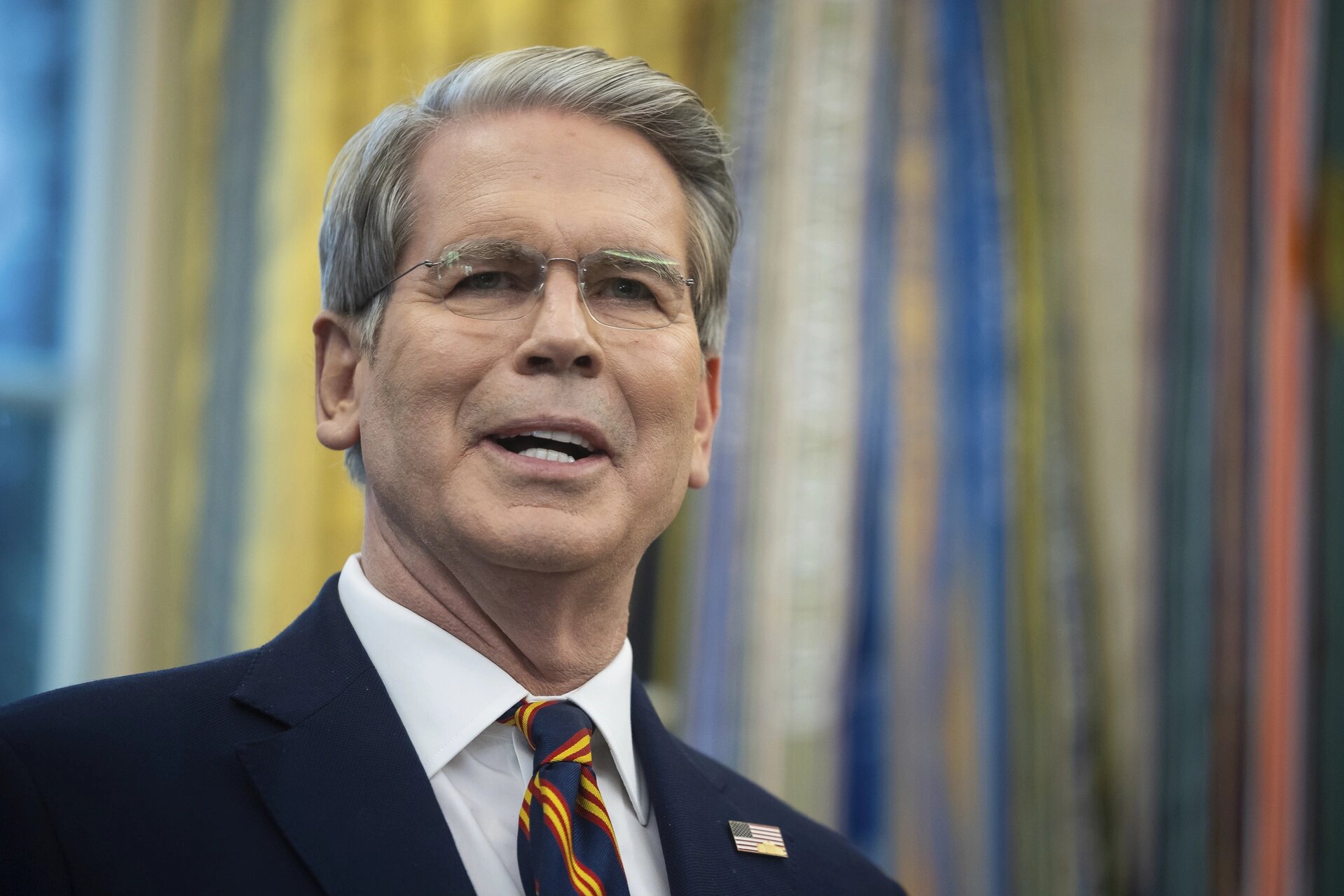

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, who is leading the search process and himself has been bandied about by Trump as a candidate for the job, wrote in a 5,000-word magazine piece that the central bank needs to commit to “scaling back its distortionary impact on markets.”

Republicans have long bemoaned the Fed’s large footprint as interfering with market discipline by flooding the financial system with cash, and Bessent has broadly framed the current relationship between the government and markets as unhealthy.

That sentiment has also been shared by other candidates on the Fed chair shortlist. “Take money out of Wall Street,” former Fed board member Kevin Warsh said on Fox Business recently, framing the position in populist terms.

I asked Bessent at a press roundtable last month whether he was looking for Fed chair candidates who would advocate for a smaller balance sheet, and he wasn’t quite willing to go there. He said his point in the magazine piece was more prospective: caution about asset purchases moving forward, not about shrinking the Fed right now.

“I was just saying that, just like antibiotics, each successive intervention has less efficacy,” he told me. He acknowledged, though, that reform was part of what he was focused on in the search.

But the only time I’m aware of Trump weighing in on the size of the Fed’s balance sheet, it was to tell them to stop making it smaller because he was worried that cash wasn’t flowing as freely in key funding markets.

“Stop with the 50 B’s,” he said in an esoteric Twitter post in December 2018, a reference to the Fed shrinking its holdings at the time by a maximum of $50 billion each month.

Some of the leading Fed candidates seem to have different instincts. Warsh has pushed to limit the central bank’s size for roughly 15 years. He’s suggested that the Fed’s balance sheet should be made smaller and argued that doing so, in turn, will allow the central bank to lower short-term rates without stoking inflation (let’s just say not everyone agrees).

Fed board member Michelle Bowman, who Bessent has also listed among the finalists, has called for “the smallest balance sheet possible,” though she cast it as a way to provide more space “to respond to future shocks or economic downturns without worrying whether there is enough room to expand the balance sheet as a potential tool.”

Don’t entirely count Bessent out for Fed chair, either. He has previously taken himself out of contention, but this is what Trump said just recently: “I’m thinking about him for the Fed … but he won’t take the job. He likes being Treasury [secretary], so we’re not thinking about him, really.”

Part of what’s going on here is that concern about the Fed’s reach seems to genuinely animate Bessent, Warsh and others.

In many ways, the Treasury chief’s argument seems to be a small-government one. In his piece for International Economy magazine, he said the Fed’s asset purchases, a policy tool commonly known as “quantitative easing,” helped make room for massive spending by Congress in the wake of Covid and fueled wealth inequality by unnaturally bolstering asset prices.

But it’s hard to believe that Trump, with his highly improvisational approach to policy, wants Fed leadership that wouldn’t throw every policy at the wall in a downturn.

Still, this might be the best shot for Republicans who want to rein in the Fed’s presence in markets.

For now, the central bank is set to stop shrinking its balance sheet on Dec. 1, a decision aimed at preventing clogs in the financial plumbing amid signs that cash is getting more expensive. That decision was supported by Fed board member Stephen Miran, who is on a leave of absence from his job as White House chief economist.

Miran argued to me that the resulting boost to markets might be limited because the central bank will also slowly replace its mortgage-backed securities with short-term U.S. government debt. That means markets will be taking on more risk associated with longer-term debt that had previously been taken on by the Fed.

As for more proactive interventions, Miran said he’s not opposed to QE when “there’s a credible and substantial, not minor, risk” to the Fed’s mandates of maximum employment and price stability.

It’s worth noting that nobody exactly agrees on the scope of QE’s effects, including how it changes market pricing and how much it stimulates the economy during a slump.

Powell, in a speech last month, suggested that, in hindsight, the Fed might have kept its asset purchases going too long in 2021, an argument that was made by some experts at the time.

But he also defended QE as a critical tool in moments when the Fed needs more ammunition to boost the economy, such as during the Covid pandemic in 2020, when markets were seizing up and unemployment skyrocketed.

The question now is what will happen in the coming months, with Powell’s chairmanship expiring next May. The voices that are more skeptical of QE have gained both power and influence, suggesting that the Fed’s response to future downturns might be different.

Still, no matter who gets the job, there’s reason to think that Trump-appointed Fed officials would feel compelled to use every tool at their disposal in a slowdown, particularly at a time when the cost of living is top of mind for Americans.

As the saying goes, there are no atheists in foxholes.